Craft is often associated with wooden chairs, pottery, and other items that are lovingly made by hand. A plastic 3D-printed object? Not so fast.

Berto Pandolfo’s work, which is featured in the new exhibit at Kensington Contemporary, Sydney, challenges this rule. His side tables show that digital fabrication technologies like 3D printing offer new possibilities to designers with a crafts ethos.

He is a part of the movement, which Lucy Johnston calls “the digital handcrafted.” This movement involves designers who use digital techniques to make desirable objects.

Craft is a controversial term, particularly in an age where machines are replacing the work that was done by hand. It’s a broad approach that is guided by tradition, materials sensitivity, and manual techniques. Pandolfo explores the place of 3D printing within this practice. The result is objects that look and feel unique rather than being mass-produced.

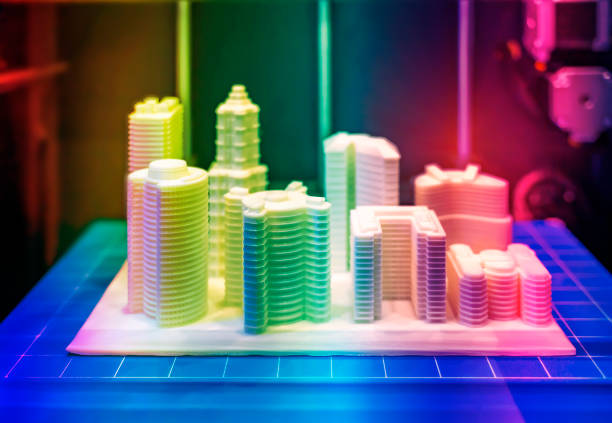

By depositing layers of material, 3D printing (also known as Additive Manufacturing) creates objects. This is a major shift in furniture design, as it represents a departure from the traditional methods of subtracting material (think carving), as well as forming or joining. Additive manufacturing, referred to by technology writers like Paul Markillie as the third industrial Revolution, was initially used to create prototypes from computer-generated designs.

Industrial designers are using 3D printing on a large scale. Direct metal laser sintering and selective laser sintering are two relatively costly processes that have proved particularly valuable in biomedical and aeronautical industries.

Fused-deposition modeling is more affordable and accessible for designers who are working on unique objects such as Pandolfo. Desktop 3D printers like CraftUnique’s CraftBot Plus are priced at a little more than US$1,000.

Pandolfo created a series of side tables for his MND exhibition using fused deposition modeling to form the legs. The legs, inspired by river stones and made from kauri, contrast with the table’s smooth surface. Wood is usually associated with rough textures. The wood, in this case, is uniform and smooth, while the plastic is rugged.

The 3D print process produces a rough surface that is usually sanded. Pandolfo chose not to do so and gave the side tables the imperfections often associated with handmade objects.

In order to take advantage of additive manufacturing’s ability to create forms with subtle irregularities, he chose the Riverstone form instead of the traditional turned wooden legs of a side table. Surface imperfections that are characteristic of the fused-deposition modeling process were not viewed as something to be avoided or a negative aspect. Instead, they were used to create a unique product.

Pandolfo’s work is part of the “digital handmade” movement because he used the limitations of 3D printing to inspire his creativity.

The marriage of 3D printing and craft is a return to pre-industrial values, where creativity and craftsmanship were a part of everyday life.

Johnston suggests that the Industrial Revolution has “resulted” in a reduced role for craftsmen. Mass production was characterized by machines and factory lines, which removed skill and imagination from the process. Creativity, once associated with handcrafted objects and crafts, became associated more with fine arts.

Pandolfo’s exploration of new technologies, materials, and forms demonstrates a blending of these supposedly opposing virtues.

This work has a wider value in that it shows how 3D printing and other technological hardware do not have to be restricted to mass-produced products. Designers and artisans can also claim this, ensuring that new meaning can be derived from our machines.